Prevalence of Adolescent Substance Misuse

Butler Center for Research - May 1, 2016

Adolescent Substance Misuse Trends Shown by a Recent Nationwide Study

Download the Prevalence of Adolescent Substance Use and Misuse Research Update.

Adolescent substance use and misuse are serious issues that contribute to significant medical, psychological, and legal consequences later in life. While it can be difficult to prevent and treat substance misuse among adolescents, scientists have discovered a number of strategies that are effective among this high-risk population.

In 2015, nearly half (48.9%) of U.S. high school seniors admitted to using an illicit drug (not counting alcohol or tobacco) in their lifetime.1 For many years, the illicit drug most commonly used by adolescents has been marijuana, and its rates of use among adolescents have increased significantly since 1991.2 Underage consumption of alcohol and tobacco also poses a significant health risk to adolescents. Within the past year, 21% of eighth grade students reported that they had consumed alcohol, and 8% reported that they had been intoxicated; these numbers skyrocket to 58% and 38%, respectively, for twelfth grade students.1 While cigarette smoking has steadily declined across all ages since 2010, e-cigarettes have become more popular than any other tobacco product, and those who use them cite experimentation and "because they taste good" as the most important reasons why they began or continue to use them.1

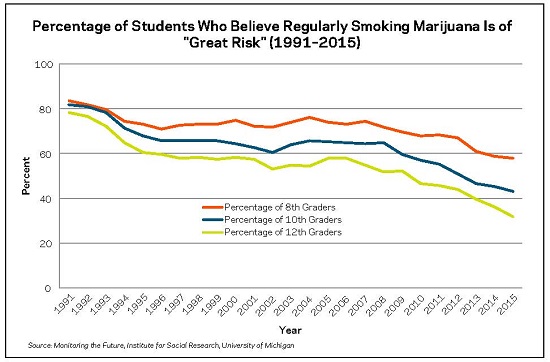

In addition to having high rates of use for various substances, adolescents have demonstrated a trend of minimizing how harmful drugs can be. Between 2014 and 2015, the perceived harmfulness of regularly smoking marijuana dropped significantly from 36.1% of high school seniors rating it as a "great risk" to 31.9%. This decline is a continuation of a 10-year trend of decreasing perceived risk (in 2005, 58% of high school seniors rated regular marijuana use as a "great risk").1

Substance use disorder rates among adolescents can be less straightforward than use statistics, as diagnostic criteria and differences in shared nomenclature can make large scale tracking of diagnoses difficult, especially since adolescents are often diagnosed using dependence and problematic use criteria developed for an adult population.2 Adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17 demonstrate alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and drug use disorders (DUDs) in fairly similar past-year prevalence rates, and the overall prevalence of these disorders has decreased slightly since 2002, from approximately 6% to approximately 3%.2 Adolescents and young adults 18–25 demonstrate much higher rates of AUDs than DUDs, although the rate of AUD prevalence has decreased since 2002, from approximately 18% to just over 12% (DUDs remained somewhat consistent, hovering between 6% and 8%).2

Recovery Interventions for Adolescents

The importance of evidence-based treatment methods rings as true for adolescents as it does for adults; however, adolescents seeking treatment for substance misuse or dependence often present unique issues that require special attention. For example, comorbidity (the presence of substance use disorders alongside one or more mental health disorders) is quite high among adolescents in treatment; a 2001 study found that 40.8% of adolescents in a public mental health treatment program also met criteria for a substance use disorder.3 Treatment interventions that address substance use as well as mental health issues are ideal for this population. Reviewers have determined that individual cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy (MET), multidimensional family therapy (MDFT), functional family therapy (FFT), and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Group (CBTG) have "well-established efficacy" among adolescent patient populations.4, 5 The American Academy of Pediatrics also recommends that adolescent treatment outcomes could be improved by incorporating adapted versions of evidence-based treatments into nonclinical settings, such as schools and youth activities, in order to maintain positive attitudes and behaviors related to substance use and provide lower-intensity interventions for adolescents with substance use behaviors that do not necessarily warrant formal clinical care.6

Preventing Adolescent Substance Misuse

Preventing drug and alcohol use and misuse among adolescents begins with setting a strong foundation in earlier stages of childhood development. Social norms, or the perceptions and expectations adolescents have regarding the behavior of others, play a significant role in whether adolescents consume alcohol or drugs (for more information on this phenomenon, see the Research Update issue on "The Social Norms Approach to Student Substance Abuse Prevention").7 Adolescents who have high levels of positive parental involvement in their lives (through school involvement or other healthy involvement) are less likely to report substance misuse in adolescence.8 Similarly, children and adolescents whose parents consistently set clear expectations about not using alcohol or other drugs were less likely to engage in dangerous drinking behavior as young adults.9 Best practices also encourage parents and other role models to often point out that many adolescents choose not to drink or use drugs, despite the perception that "everyone is doing it."7 School- based programs that globally promote healthy habits among disadvantaged children and their parents (including increased healthy parental involvement and expectations) have consistently demonstrated success in increasing positive, healthy behavior among adolescents and young adults, including reduced substance use and misuse.8, 10, 11

Summary

Rates of adolescent substance use suggest that prevention and intervention efforts specifically geared toward young people are critical. While specific trends in substance use vary a great deal among adolescents over time, a number of clinical and school-based evidence-based treatment and prevention efforts have been shown to be effective in reducing substance use among adolescents, regardless of the substance being used or whether a substance use disorder is present. Parents and role models who consistently establish healthy social norms regarding alcohol and drug use throughout childhood and adolescence set the strongest foundation for preventing unhealthy substance use behaviors later in life.

Hazelden Betty Ford Experience

Hazelden Betty Ford offers a wide variety of services for adolescents, including sites and programs dedicated specifically to adolescent patients. Our Hazelden Betty Ford in Plymouth, Minnesota, treatment site caters to patients between the ages of 14 and 25. We offer residential and outpatient programs and services that utilize evidence-based practices that have demonstrated effectiveness in adolescent populations. Hazelden Betty Ford also offers programs for parents and siblings that provide education and support for the loved ones of adolescents who have been affected by addiction to drugs and alcohol.

In 2010, 628 young people received residential treatment at Hazelden Betty Ford in Plymouth, and 94% of these patients reported having at least one other alcohol and drug treatment experience prior to coming to Hazelden Betty Ford. The rate of co-occurring disorders in this group is also extremely high, with 93% having another psychological disorder (such as anxiety or depression) in addition to substance dependence. Because so many adolescents with substance use disorders present with psychological problems, Hazelden Betty Ford treatment plans are designed to address both disorders.

Questions and Controversies

Question: Isn't it better for parents to have relaxed attitudes about drug and alcohol use so children can come to them to talk about their use, or so they drink at home in a safe environment instead of somewhere else?

Response: While many parents believe it is safer to allow their teenagers to drink at home, or to promote a relaxed attitude about drug and alcohol use to avoid children from "sneaking around," it can actually be much more harmful in the long run. Parental expectations over a child's development set the stage for perceived social norms that adolescents and young adults use to determine whether certain behaviors are acceptable.8 These norms play a major role in predicting whether adolescents and young adults will engage in risky or unhealthy drinking and drug use behavior later on in life.9

How to Use This Information

Parents: Take an active role in educating your children about the dangers of substance misuse and have frequent conversations about what they are doing and with whom they are spending time. Establish a clear expectation in your home early on in your child's life that drinking and drug use are not acceptable and talk to your kids about perceived social norms versus actual social norms among their peers.

Health Care Providers: All routine medical checkups for children and adolescents should include a screening test for substance use. Regular medical visits provide an excellent (and underutilized) opportunity for screening and brief intervention with adolescents engaging in hazardous use. Many brief screening tools have been developed and evaluated for use within an adolescent population.

References

- Johnson, L. D., O’Malley, P. M., Miech, R. A., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2016). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research.

- Peiper, N. C., Ridenour, T. A., Hochwalt, B., & Coyne-Beasley, T. (2016). Overview on prevalence and recent trends in adolescent substance use and abuse. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America (in press).

- Aarons, G. A., Brown, S. A., Hough, R. L., Garland, A. F., & Wood, P. A. (2001). Prevalence of adolescent substance use disorders across five sectors of care. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(4), 419-426.

- Tripodi, S. J., Bender, K., Litshge, C., & Vaughn, M. G. (2011). Interventions for reducing adolescent alcohol abuse: A metaanalytic review. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 164(1), 85-91.

- Waldron, H., & Turner, C. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 238-261.

- Caywood, K., Riggs, P., & Novins, D. (2015). Adolescent substance use disorder prevention and treatment. Colorado Journal of Psychiatry and Psychology: Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 1(1), 42-49.

- Vasquez, D. & Fay, H. (2015). The social norms approach to student substance abuse prevention. Research Update. Center City, MN: Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation.

- Hayakawa, M., Giovanelli, A., Englund, M. M., & Reynolds, A. J. (2015). Not just academics: Paths of longitudinal effects from parent involvement to substance abuse in emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58, 433-439.

- Neighbors, C., Lee, C. M., Lewis, M. A., Fossos, N., & Larimer, M. E. (2007). Are social norms the best predictors of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(4), 556-565.

- Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Robertson, D. L., & Mann, E. A. (2001). Long-term effects of an early childhood intervention on educational achievement and juvenile arrest: A 15-year follow-up of low income children in public schools. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 2339-2346.

- Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., Ou, S. R., Arteaga, I. A., & White, B. A. B. (2011). School-based early childhood education and age-28 well-being: Effects by timing, dosage, and subgroups. Science, 333(6040), 360-364.